Refuturing the Soil 2. – Mapping the other side of modernity and peace, guided by the radioactivity of Shinkolobwe’s uranium ore – (2024-ongoing)

#Collaboration #Exhibition #Research

In relation to the project, I’ve contributed an article to Rekto:Verso summer issue 2025: ‘The Defutured Soil of Shinkolobwe’

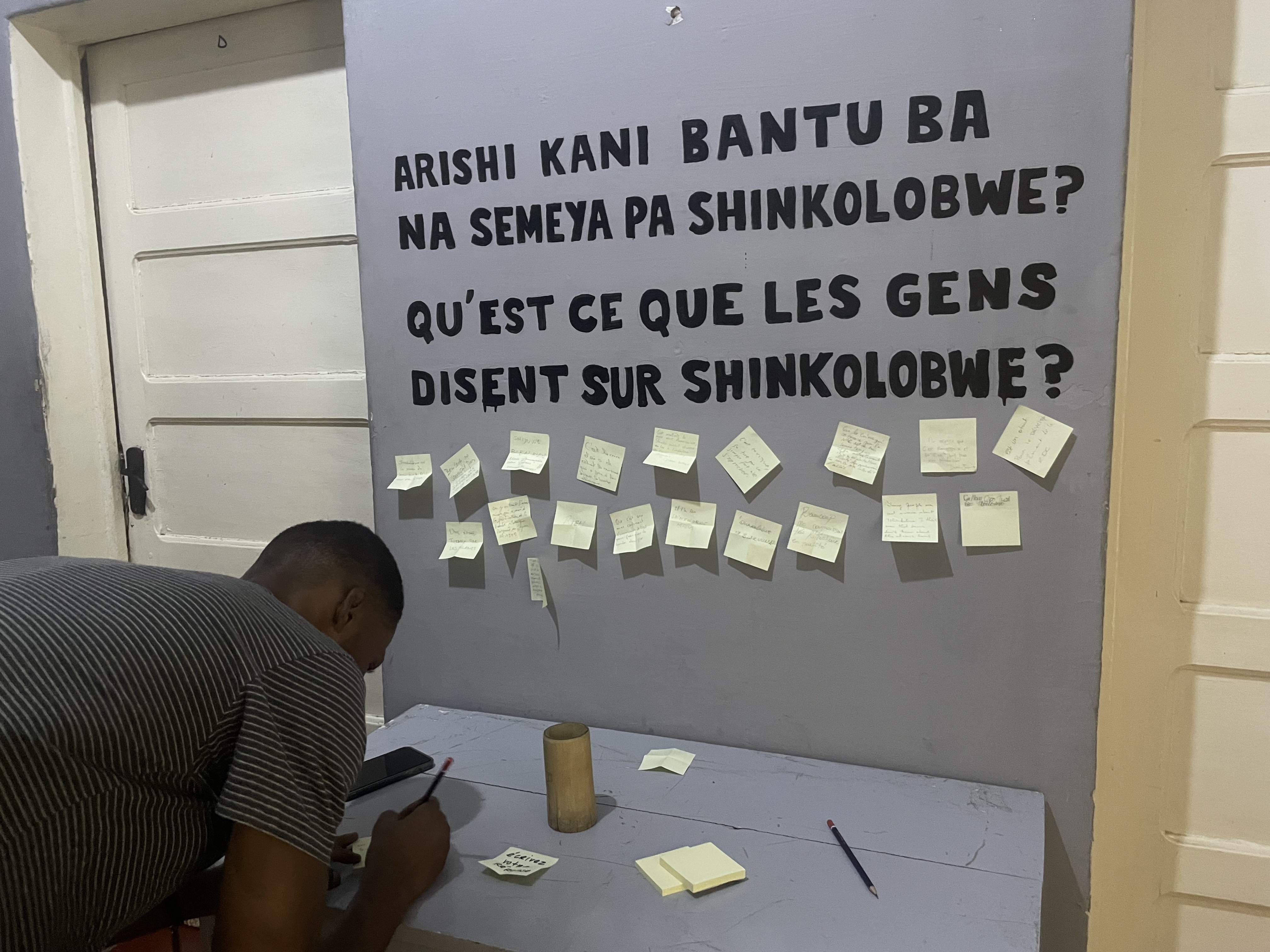

Refuturing the Soil 2. – Mapping the other side of modernity and peace, guided by the radioactivity of Shinkolobwe’s uranium ore – (ver2.) in the group exhibition, “SHINKOLOBWE: BETWEEN POWER AND MEMORY, Gallery G, 29 July to 10 Aug 2025

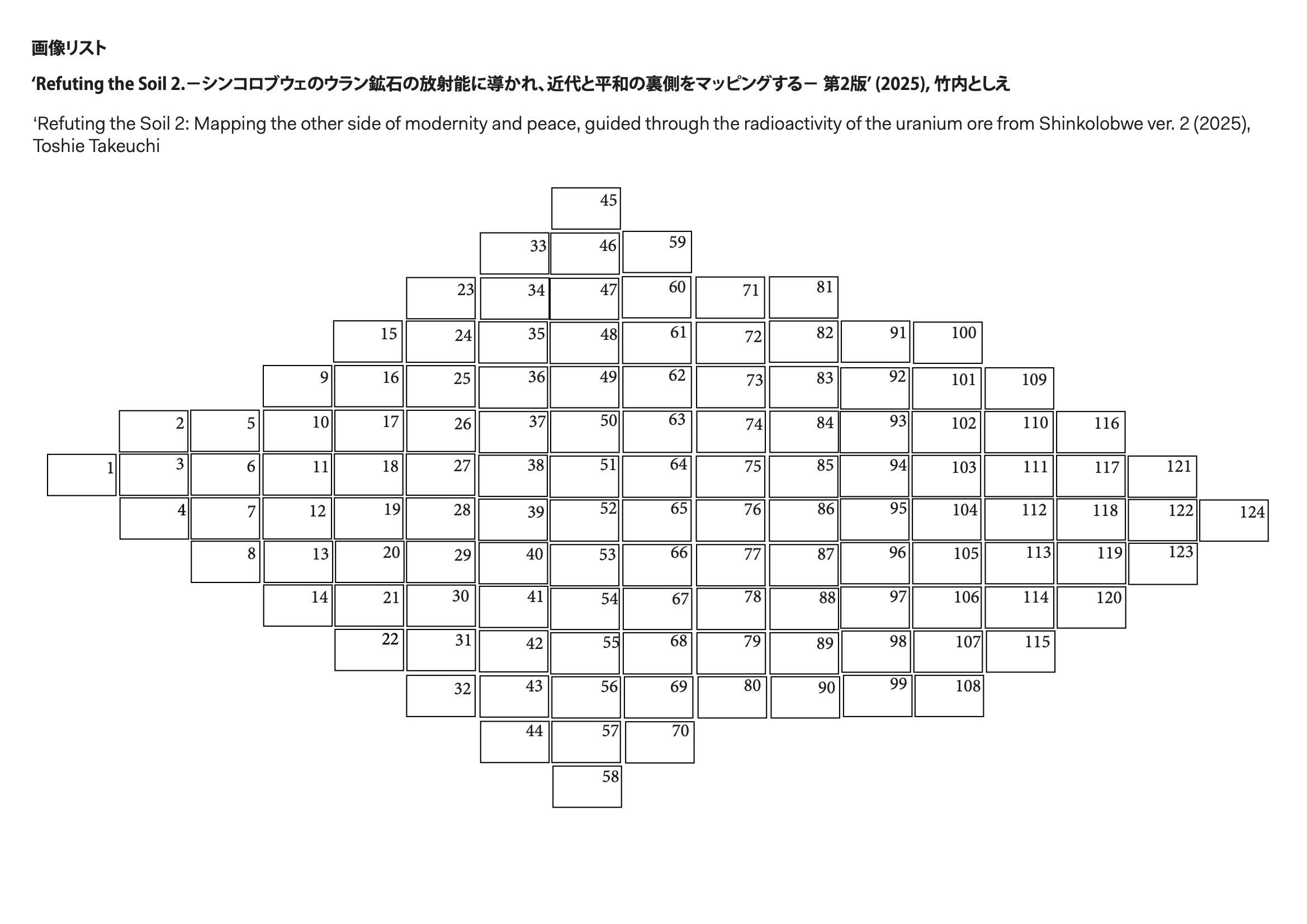

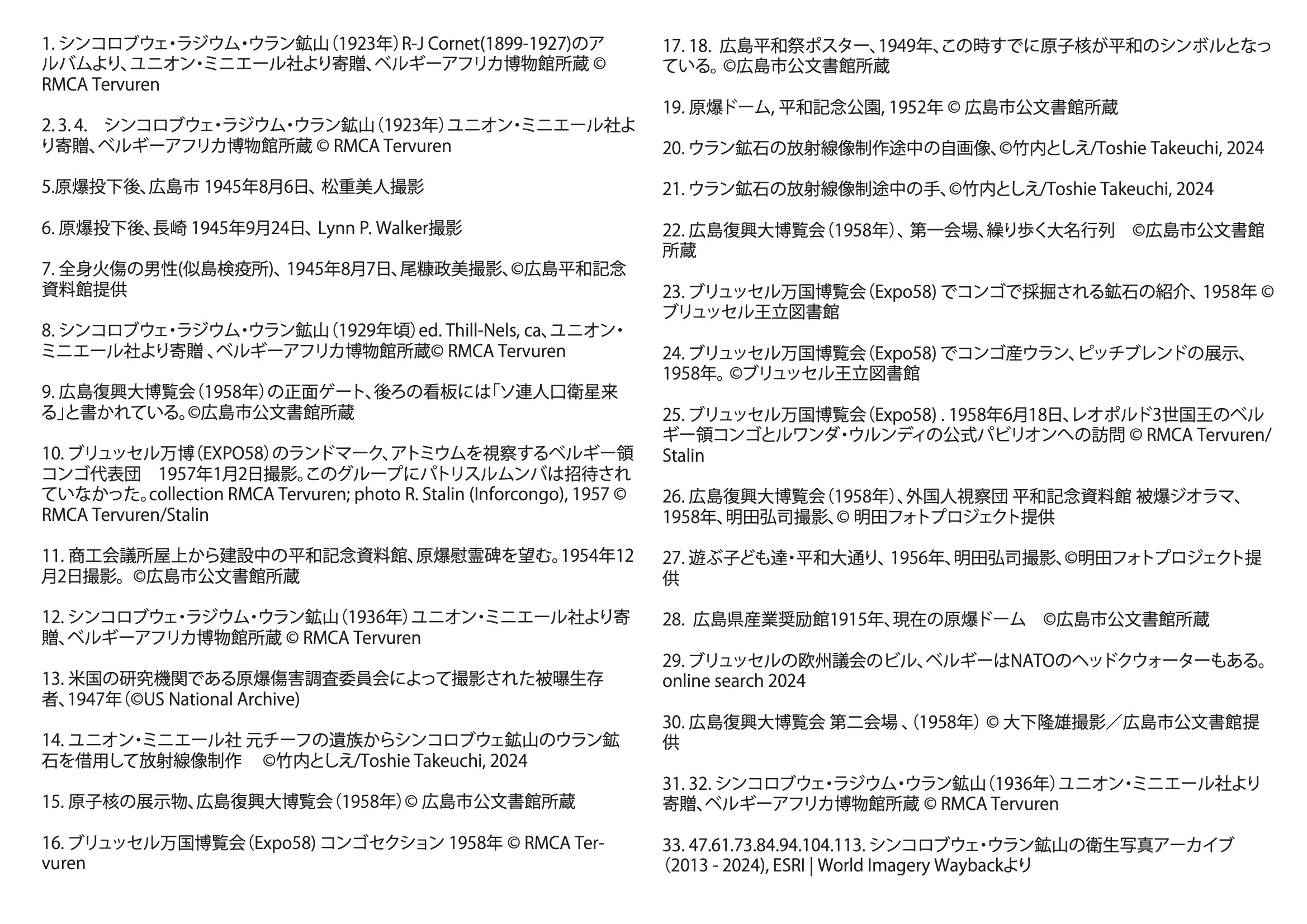

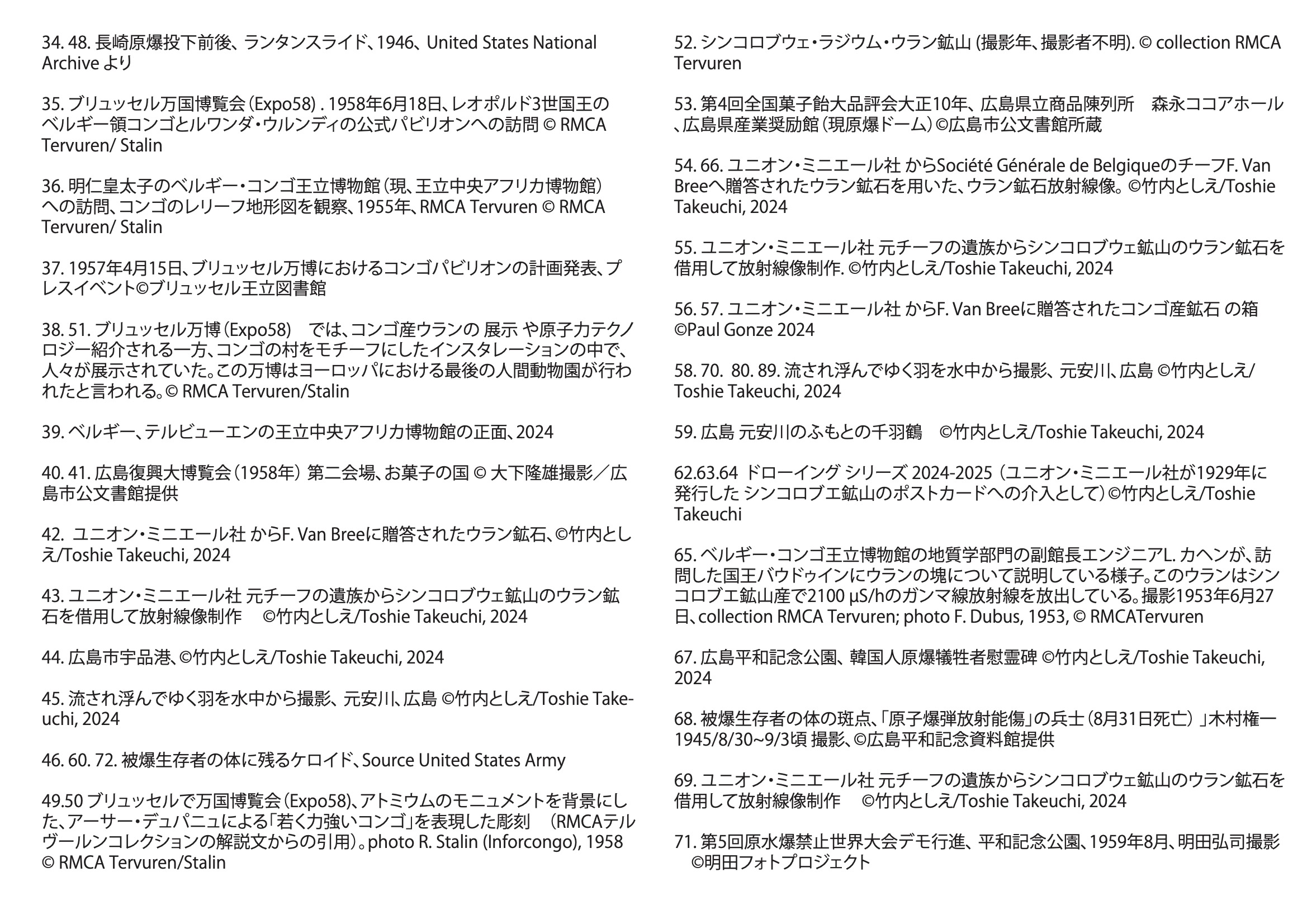

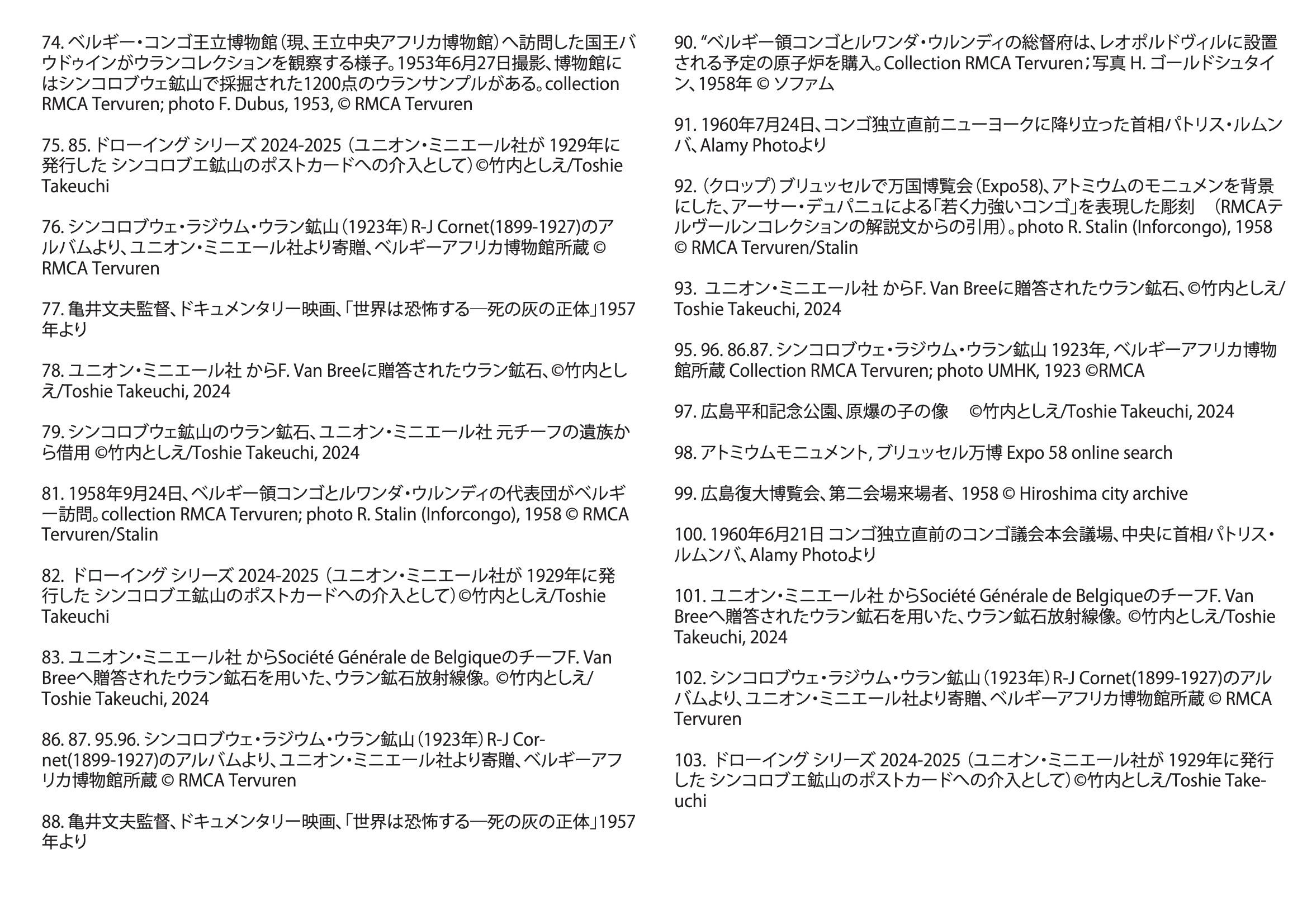

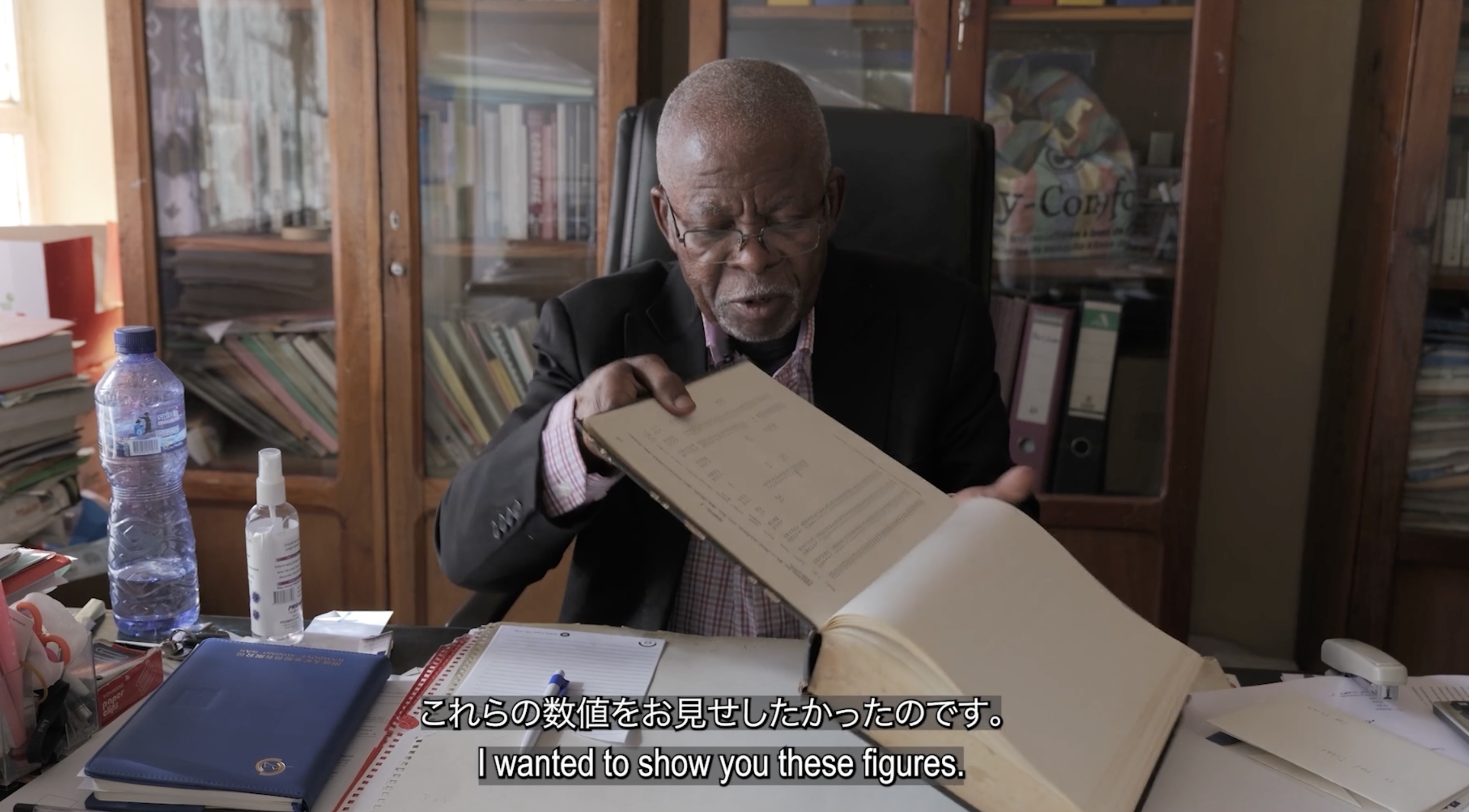

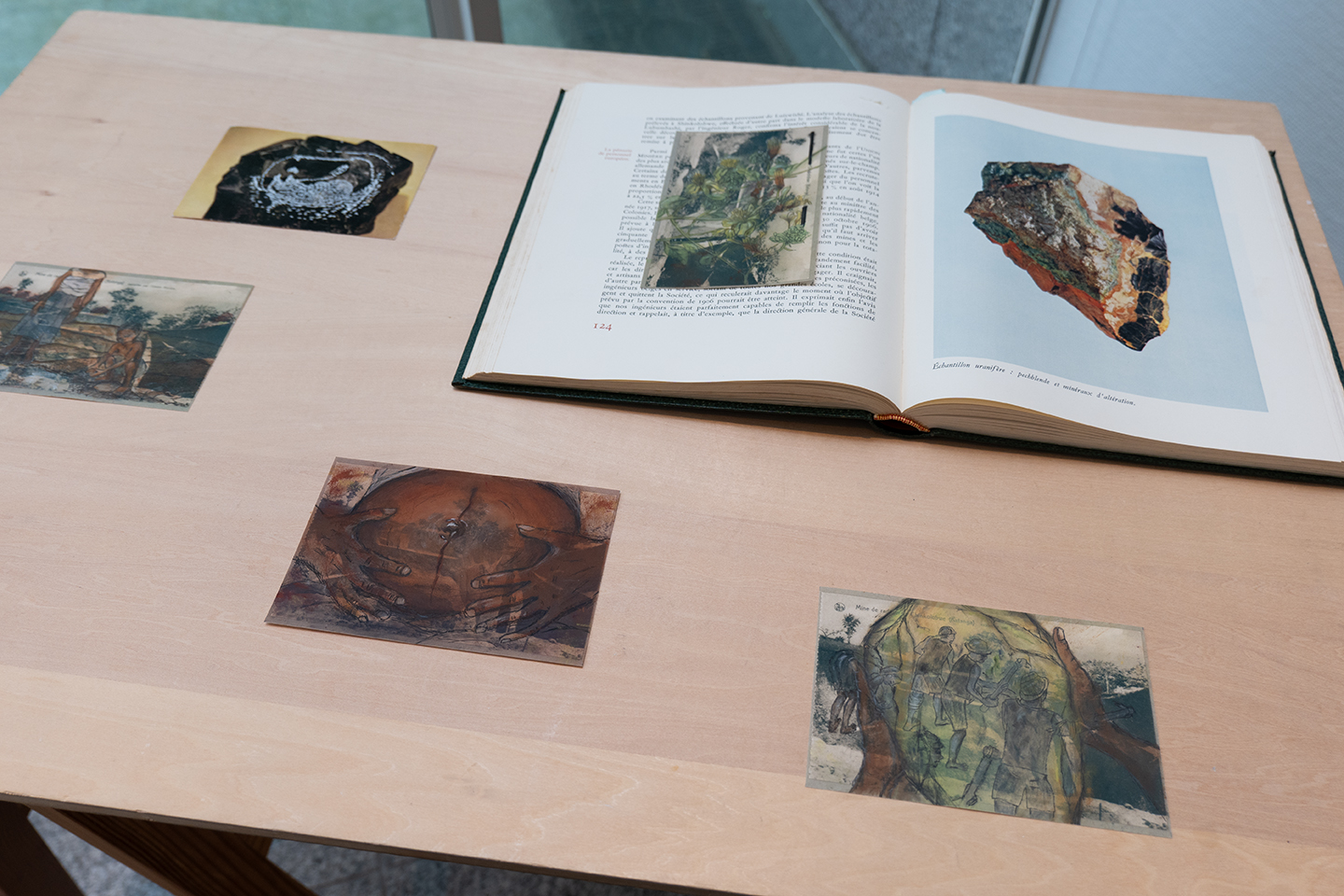

The installation consists of 129 postcard-size images on the wall (details are different depending on versions), created in combination with the artist’s own works, historical archives and satellite archives. It exhibited alongside a series of hand-drawings and a video interview. The work has been a part of ‘Shinkolobwe Between Power and Memory’, which is a collaboration and artistic conversation between 3 artists from Congo, Japan, and the USA, about DR Congo’s Shinkolobwe mine, source of the uranium used to develop the first atomic bombs. (Read the description of the overall project here)

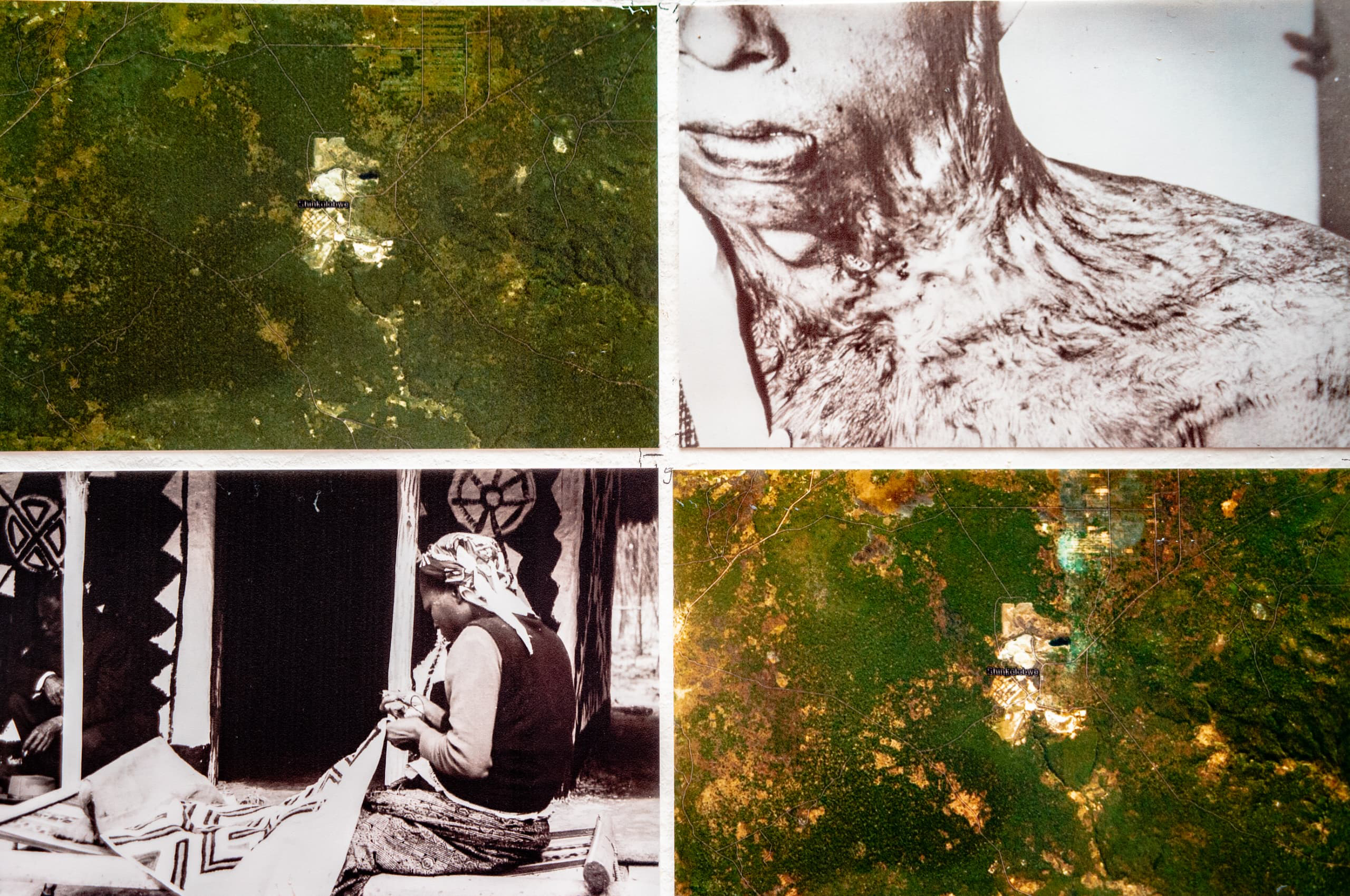

My work ‘Refuturing the Soil 2. – Mapping the other side of modernity and peace, guided by the radioactivity of Shinkolobwe’s uranium ore’ imagines the erased memories and experiences of the miners and their families at the Shinkolobwe mine. It aims to make visible the continuity of radioactive contamination, mineral exploitation around the mine. While tracing the evolution of the mine site from its colonial dawn to its historical abandonment into the contemporary era of copper and cobalt extraction, this work weaves in historical events from the post-WWII development in Japan and Europe, with particular focus on modern/colonial duality of nuclear history.

The DR Congo was paradoxically both a visible and invisible part of post-war development and its significance shaped by the whims of U.S. and European interests. This colonial paradox is also clear after the Manhattan project. E.g. at the Brussels Expo 58, the colonial ethnological exhibition was still exercised. Congolese people were exhibited in fake villages mimicking traditional Congolese houses, alongside the Atomium tower. On the other side, in Japan, U.S. research dehumanized atomic bomb survivors by using them as scientific research materials of residual radioactivity. Simultaneously, these survivors were placed in a position to promote nuclear power (during the Atoms for Peace campaign) to all over Japan through festivals and expos like the Hiroshima Reconstruction Expo 58 (Hiroshima Fukkō Dai Hakurankai 58). The work tries to deconstruct the narratives and aesthetic of modernity and peace.

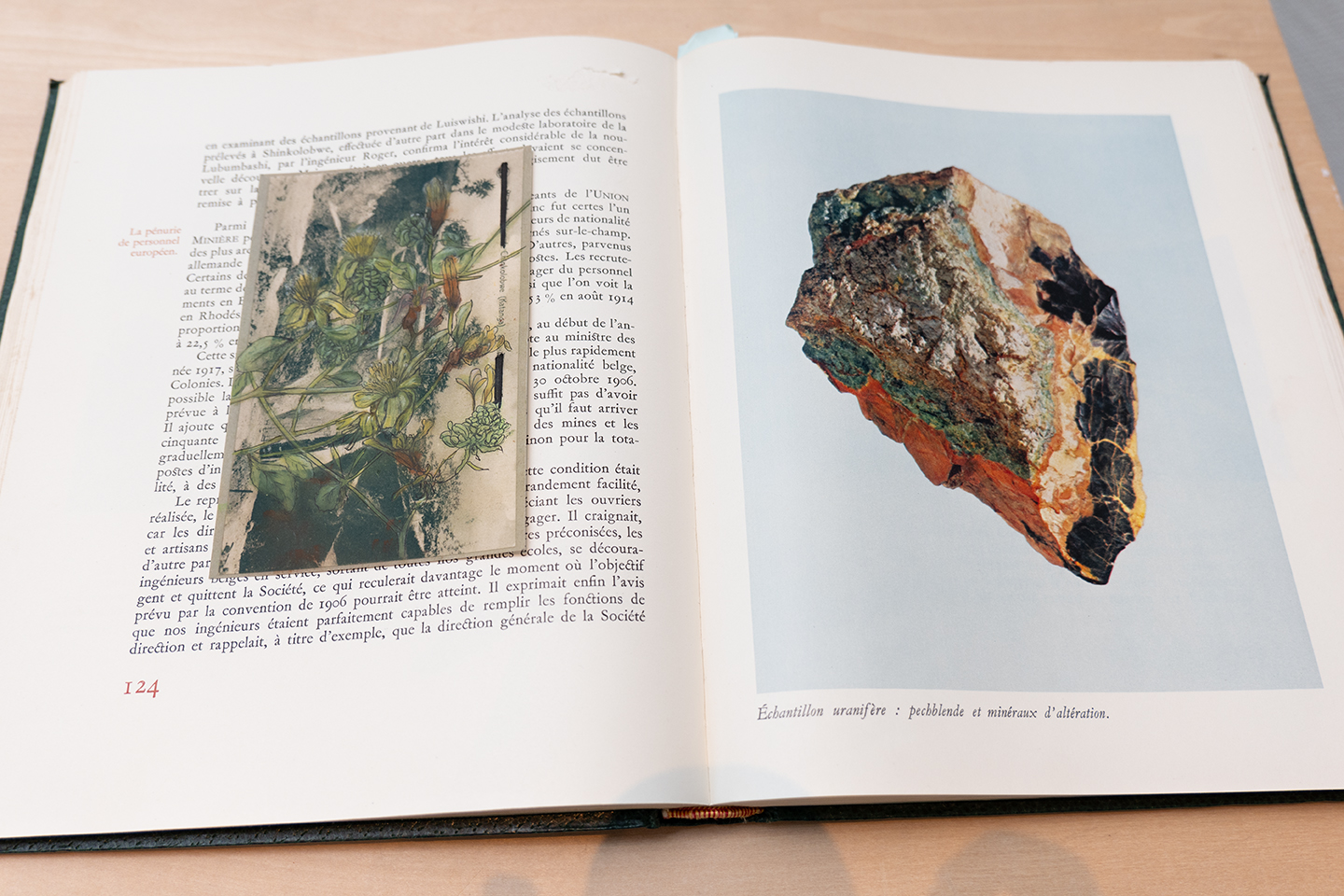

The images of the installation includes: a series of photos of autoradiography of uranium ore from the mine, which was conducted by the artist, a series of hand-drawings on colonial postcards of the mine published by Union Minière du Haut-Ka tanga in 1923, a series of photos of uranium ore and field research in Hiroshima. Also the installation includes; a series of satellite images around the mine (2014-2024), a series of historical archives from the following contributors: ©Collectio RMCA Tervuren, ©RMCA Tervuren/Stalin, ©Sofam, ©Koushi Akeda, ©Hiroshima city archive, ©Brussels Royal Library,©Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and United States Army, ©Google, ©ESRI | World Imagery Wayback.

*I wrote about the history over the Shinkolobwe mine, from the period of colonial extraction of radium to the Manhattan project to the current situation of the mine. It can be read in my research page.

Refuturing the Soil 2. – Mapping the other side of modernity and peace, guided by the radioactivity of Shinkolobwe’s uranium ore – (ver1.) in the group exhibition, “SHINKOLOBWE: BETWEEN POWER AND MEMORY, Lubumbashi Biennale, Picha, 29 Oct to 29 Nov 2024

Monologue: Autoradiography of uranium ore – anecdote and thoughts:

There are many autoradiography images of uranium ore available to view on the internet, like the beautiful image created by the science photographer, Fritz Goro in 1946. He used the ore from Northwest Territories in Canada. Though I searched a lot, I didn’t find any that indicated that their images were created with Shinkolobwe’s uranium. I was almost hunted by this subjective fact and started seeing an analogy between this – no radiation images of Shinkolobwe’s ore are available – and that – no collective memories of the Shinkolobwe mine or no archived documents can be found to trace radioactivity impact on the miners of Shinkolobwe mine. The Union Minière du Haut-Katanga didn’t seem to make records about the effects of radioactivity exposure on their miners. But do we believe that?

In Japan, the story of Shinkolobwe is still new to many. For a long time, people thought the uranium used for the atomic bombs dropped on Japan were exploited from Canada.

The strategic narrative. Visual cultural control.

Permanently effective.

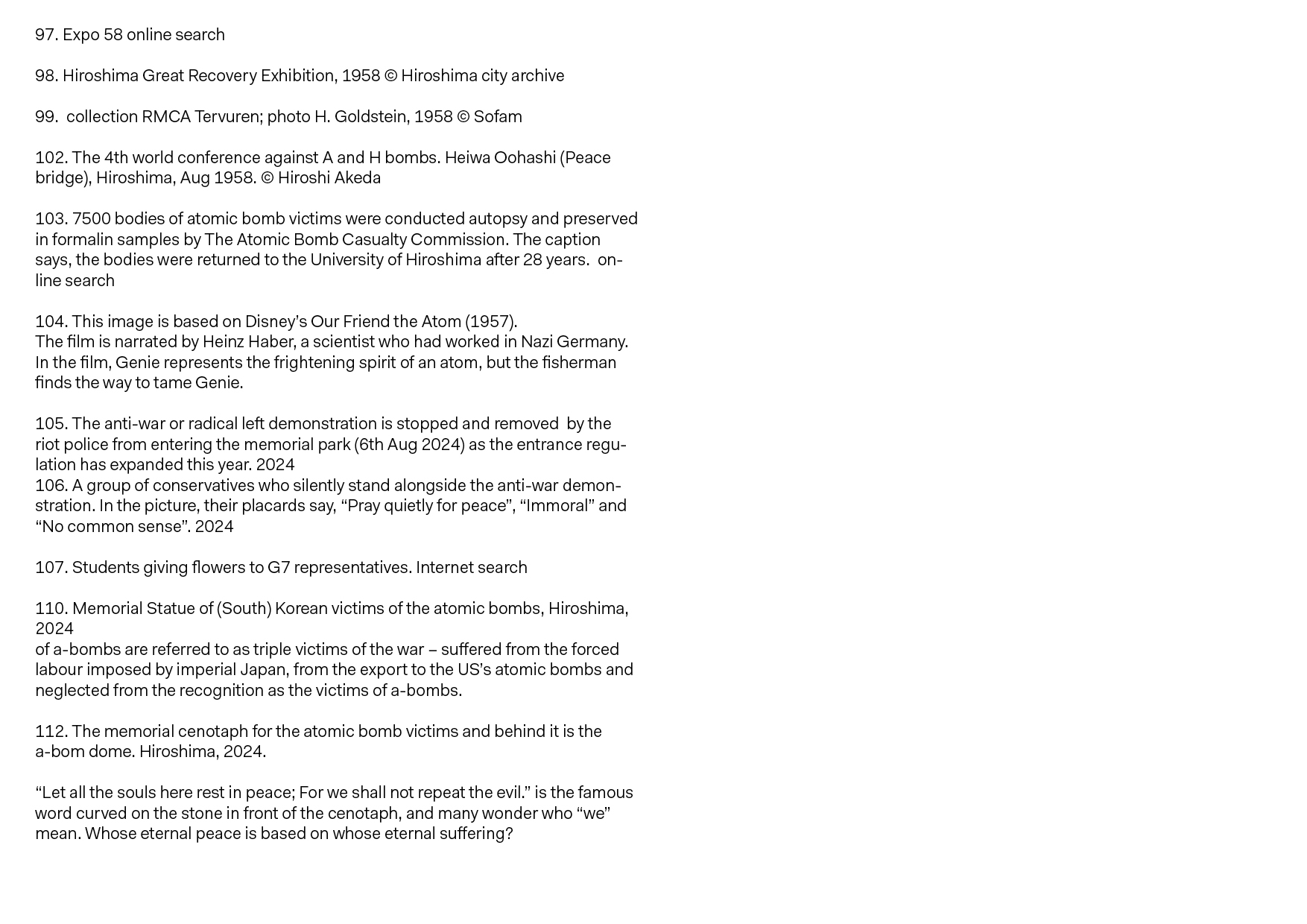

I felt creating radioactive images of Shinkolobwe’s uranium ore would be my essential starting point to “expose” this erased history of Shinkolobwe and, even better, if the exposure can be made with colonial collections. Then I was excited and thought, if possible!! I want to do it with that gigantic uranium block collected in the Africa Museum in Brussels. It is a huge block of uraninite. The block that were once exhibited as the beautiful/exotic/fascinating/scientific object in front of the important guests. The block that is however forbidden to be near by any public now, forbidden to be photographed or to be even known where it is stored. Then soon I got to know that it was a fool’s idea anyway. That uraninite block itself emits 2100 µS/h gamma radiation. If I am close to it e.g. for 30 mins, it would already exceed the limitation of annual exposure to radioactivity. Then, I thought of the bare hands of the invisible miners,

who dug and carried the block from the mine,

to the wagon,

to the rail and it probably arrived at the scientific laboratory of the company U.M.H.K.

or

to the train,

to the ship and it directly arrived at the museum?

How much radioactivity were they exposed to? Their bare hands, probably full of radioactive dust covering their wounds, were they able to wash it off before having some meal? Does washing hands even make sense? In question to myself – though a naive question, considering the labour condition in colonial time, or seeing the labour condition currently, right now, happening in the mines in the Congo – did they even have any access to non-contaminated water?

In the museum, I was told that there was no inventory available for this gigantic uraninite block. At that moment, no one in the museum seemed to know how and when it was brought to the their collection. Only known is that it was dug from the Shinkolobwe mine like all their other uranium collections in the museum. They have about 1200 uranium samples from Shinkolobwe mine.

Beautiful uranium, shiny orange, yellow, green, black, sometimes pink together with cobalt. Geologists get excited with your beauty and formation.

Beautiful uranium seduced scientists with your hidden energy.

Beautiful uranium, you were disturbed, separated from your mother soil. Your energy penetrated their bodies. Your rage melted down their bodies. Who bursted your atom like that?

50.000 to 100.000 to the instant death

About 210.000 within a few months.

Total 690.000 of atomic bombs victims, of which about 10% are people from Korea brought by colonial Japan. They shouldn’t have been removed from their mother land.

Beautiful uranium, your radioactivity is still all over the world and will forever emit. How many more victims will be created?

Katasumbika

is the word I learned from Petna Nadaliko, my admired film director.

Katasumbika: don’t lift up from the ground.

Katasumbika: precious mineral.

Don’t separate them from their indigenous ground.

Time passes, tones of communications, struggles back and forth,

Because of the museum’s regulations, I wasn’t allowed to interact with their uranium collections. Ok. Fine. I am not a scientific researcher. But I think you have some problems. What about art?

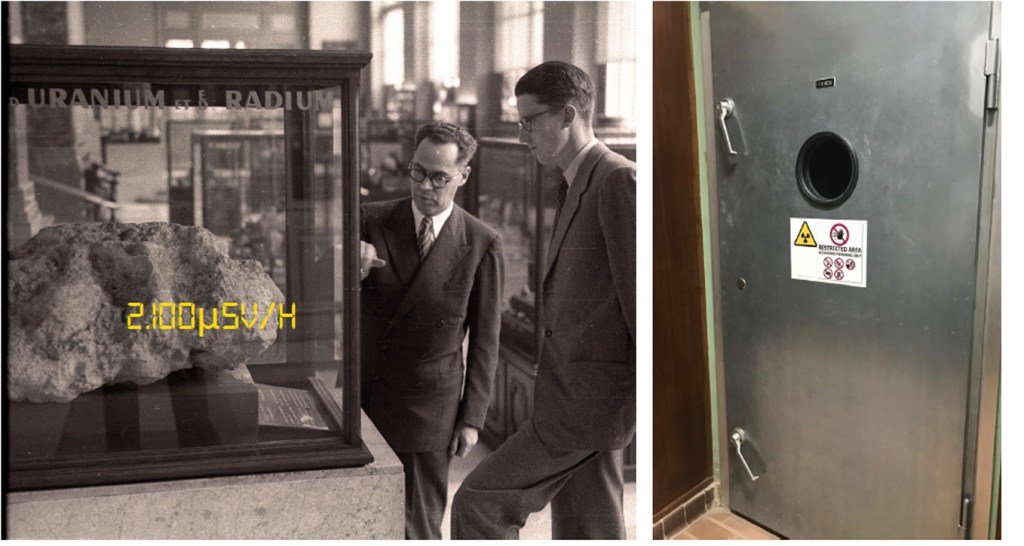

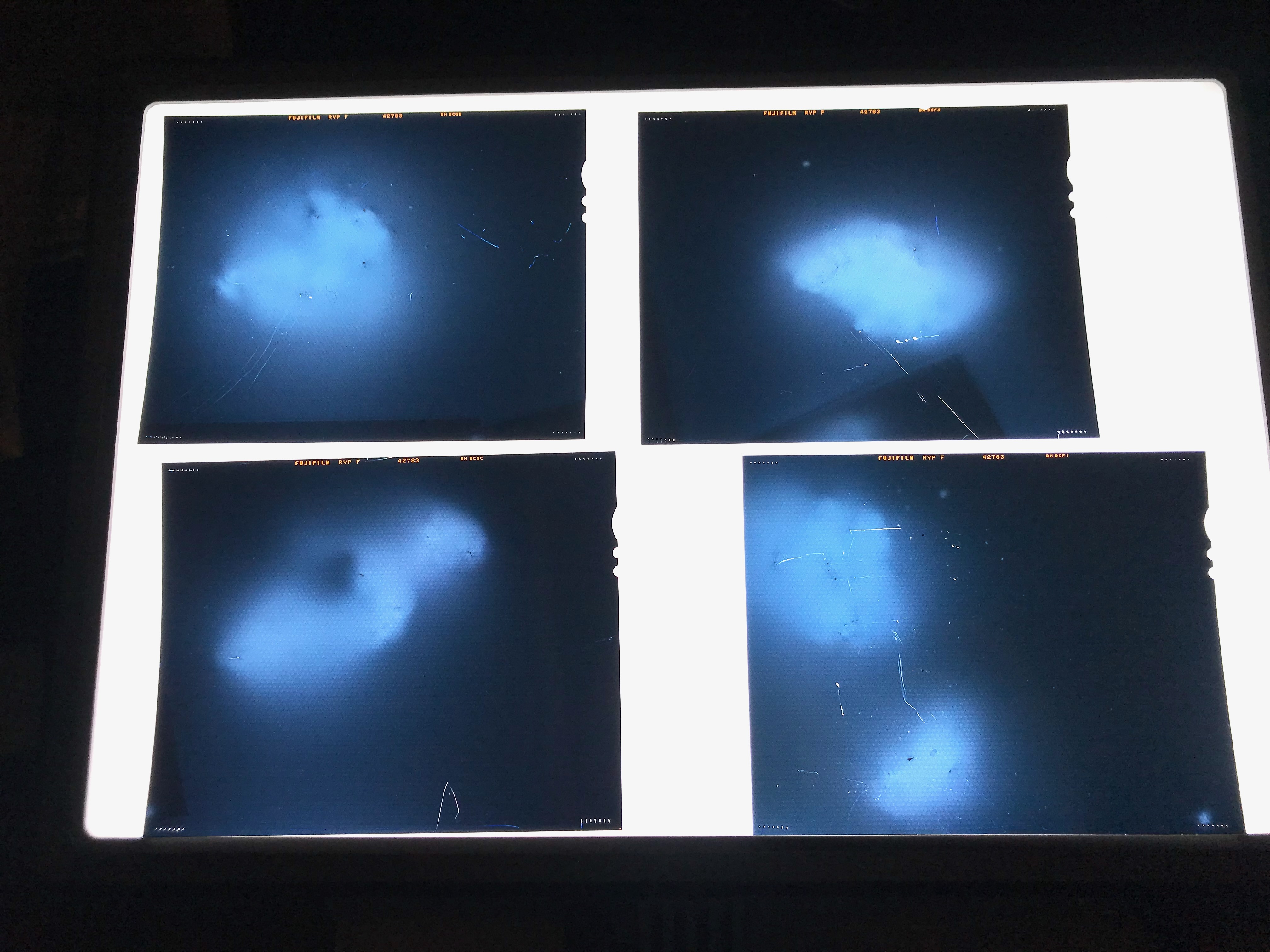

Luckily I was introduced to a private collection of uranium ore samples. Some of Paul’s collections were inherited from his great uncle, Firmin van Bree, former director of the Société Générale de Belgique (1924-). That wooden box full of beautiful minerals from Katanga was a honourable gift from Société Générale to van Bree. And, Paul’s other collections were inherited from his father, chief of U.M.H.K. I selected 7 or 8 samples and brought them into the basement in Paul’s house. It had to be completely dark to be sure that I would succeed in my autoradiography experiment, though later I realised that there was a much easier way to do this. If I sealed each photographic sheet into a black bag and placed the uranium on top of the bag, then I could have done this under day-light. But I didn’t know. In the darkness, I was placing the samples by feeling, actually for many hours. I didn’t measure how strong radiation these samples emit. At least I wore a working suit and a face mask so as not to inhale uranium dust. I was still in sort of constant paranoid about radioactivity exposure.

I tried not to think about the consequences to my body.

I thought of the article I read somewhere. It was about genetic mutations witnessed in the area of Shinkolobwe mine and the testimony by a gynaecologist. In that situation the only choice for him was to recommend abortion to those mothers.

Then of course, I thought of the babies who didn’t make their way to this world.

The mothers, who were told to terminate their babies, without being told why but they were aware of why.

The fathers, who were digging in the mine, without gloves, without masks, without even shirts and then he returned home together with uranium particles.

I was thinking about the wind that contained uranium dust. It blew into their home. But none of these were and are visible. All of these were in silence?

What about cough?

Convenient invisibility.

Convenient disconnections.

Convenient segregation. They knew it already since the 20s.

The exposure times of the autoradiography experiments were, 12 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours.

As long as the uranium was placed, the exposure had continued.