Erasure: Chronology of the colonial industrial mining at Shinkolobwe to the Manhattan Project and Now?

#History #Research

Above: The Shinkolobwe mine in 1923, collection RMCA Tervuren; album R.-J. Cornet,1899-1927

The Shinkolobwe mine is located 145 km northwest from Lubumbashi in the south-eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, in the region of Katanga along the border with Zambia. Katanga is one of the most mineral rich regions in the world with its cobalt, copper, tin, radium, uranium and diamond deposits. The history of the Shinkolobwe mine is often traced back to 1915, when British geologist Robert Rich Sharp unearthed a radioactive mineral deposit at the site. He was employed as a prospector and surveyor by Tanganyika Concessessions, a British mining and railway company, which operated in Northern Rhodesia and the Congo Free States. Tanganyika Concessions partly owned Union Minière Haut Katanga, a mining company operating in Belgian Congo. Union Minière had a monopoly on mining rights in Katanga province. As a result Katanga was, in effect, more like a separate independent empire run by the company. (After the independence of DR Congo, Union Minières became Gécamines, a Congolese state-owned mining company. The share that was not incorporated into the reform was subsequently absorbed by Société Générale de Belgique and later became Umicore in Belgium).

Union Minière started their industrial mining at Shinkolobwe in 1921 for the exploitation of radium from uranium ore, Uraninite. Radium was a rare and expensive mineral, used in application such as cancer treatment and as a self-luminous paint for watches, clocks, and instrument dials. For decades, Union Minière dominated the world market of radium with Shinkolobwe’s ore, but the use of uranium was limited until the outbreak of World War II. At Shinkolobwe, the company mined the mass uranium soil, then sorted out only high quality ore for transport to Belgium, where radium was extracted at their refining facilities in Olen. As a result, the vast amount of the uranium bearing ore, which was highly radioactive, was discarded and piled into massive waste heaps at the Shinkolobwe site.

Above archives from collection RMCA Tervuren

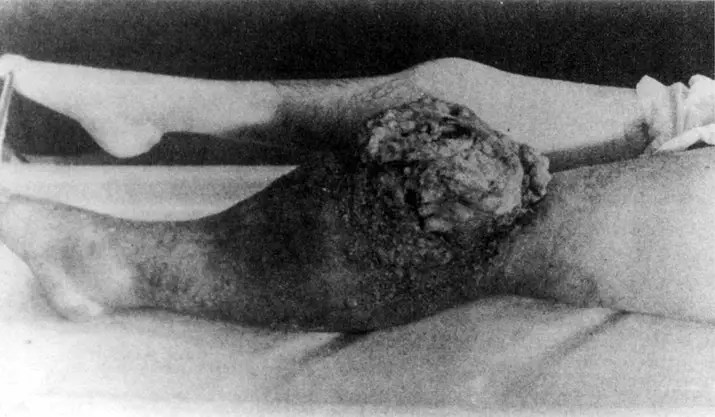

In the west, occupational disease from radioactive material had already been identified by the 1920s. For example, in the United States in 1928, a lawsuit was filed by so-called “Radium Girls”, who were dial painters for clock manufacturers. As they were instructed to lick their brushes to draw a fine point of the dials, they unknowingly ingested radium. Their exposure to radioactive material caused serious sickness, including anemia and bone cancer. As a result of their decade-long legal battle, which they ultimately won, and an extensive study by the U.S. Public Health Service, the toxic effects of radioactivity became widely recognized. By the 1940s, radium-dial painters were instructed in proper safety precautions and provided with protective gear. Furthermore, at the uranium mine Jáchymov in Czechoslovakia, prolonged inhalation of radioactive radon gas caused lung cancer among miners. The connection between radon, radioactivity and cancer had been already identified long ago and the landmark report was published The American Journal of Cancer in 1923. However, in Belgian Congo, safety precautions and medical knowledge were ignored.

Miners at the Shinkolobwe, under the colonial regime, were digging and sorting the highly radioactive uranium ore with their bare hands and feet. As mentioned above, the radioactive waste was piled up like a mountain, likely contaminating entire area, including the drinking water. The Congolese workers lived in segregated areas, separate from the Belgian workers and in close proximity to the mine. Moreover, there was no hospital in the area to provide medical care.

The World War II and Urgency to Obtain “freaking powerful” Uranium

In 1939, when world war II was about to begin, the engagement on the scientific research to build atomic weapons became very urgent among the imperial nations such as the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany as well as Japan and later the Soviet Union. Luc Barbé – a former Belgian politician in the preceding Green party and the author of ‘Belgium and the Bomb/La Belgique et la bombe (available in French and Dutch) writes, “Union Minière was perfectly prepared” for this situation. On May 1939, Edgar Sengier, the managing director of Union Minière and Société Générale de Belgique had a meeting with Frédéric Joliot-Curie, physicist and a son-in-law of Marie Curie, to discuss about sales of uranium. At that time, the team of Joliot-Curie had just applied for patents for the experiment of energy and bombardment from nuclear fission. This made Sengier become very enthusiastic as he had finally found the financial revenue from the reserves of uranium ore from Shinkolobwe. France bought seven tonnes of uranium dioxide from Union Minière and set up a company to produce bombs through nuclear fission. But the project became impossible to carry out, when Nazi Germany invaded France, although France managed to transport some of the acquired uranium to Morocco.

On August 2 in the same year, Albert Einstein signed the famous “Einstein–Szilard letter” to F. D. Roosevelt. The letter suggested taking immediate action to speed up the experimental work on a “nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium” to construct the new bombs, which are extremely powerful that a single bomb would “well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory”. To succeed this, the letter hinted that the most important source of uranium is deposited in the Belgian Congo. The letter suggested taking immediate action, because otherwise Germany could surpass this race to develop atomic bombs by obtaining the Congolese ore. Then the US atomic committee was immediately set up.

In May 1940, Belgium was occupied by Germany. Uranium stocks that remained both in France and Belgium were transported to Germany by train. Meanwhile, as Sengier expected high demand for Congolese uranium and knew its great potential, he had secretly arranged a transport of the uranium stock to England and the United States. By the end of 1940, 1200 tons of uranium ore was shipped to New York. 2 months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Roosevelt had given a go-sign to the atomic program. Japan started the total war against the allies, while expanding its occupation and invasion to Southeast Asia on 7th December 1940.

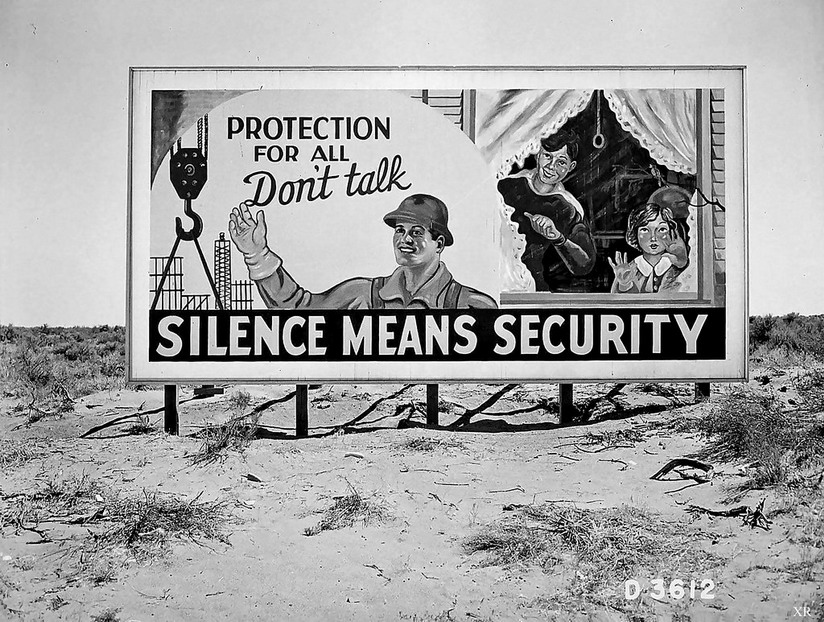

The atomic program obtained official approval and the Manhattan project was officially formed in August 1942 with Leslie Groves as the head of commander and Robert Oppenheimer as the head of Los Alamos Laboratory. The US immediately acquired 1200 tons of Congolese uranium ore which was already stored in N.Y and then 3000 tons more stored above ground at the mine in Shinkolobwe site. The US wanted to buy all the rest of uranium reserved at the mine, as the ore was astonishingly powerful, containing exceptional concentration of uranium oxide as much as 65%, whereas uranium ore mined in other places contained maxim a few percent of uranium oxide. The US also demanded Union Minière to re-open the mining operation at Shinkolobwe, because the mine had been closed since 1937. Groves knew that the one who develops this nuclear weapon first would win the war and dominate the rest of the world. The Manhattan project was like a ‘separate secret state’ as British historian Susan Willams points in her book, Spies in the Congo: America’s Atomic Mission in World War II, 2016. During the Manhattan Project and the first decades of the Cold War, the US made their monopoly on the acquisition of Congolese uranium from Union Minière. The operation in the Shinkolobwe mine became hidden as a top secret. From 1943 until 1945, the US sent OSS agents (Office of Strategic Services, the former CIA) to the Congo to supervise at the mine and to ensure that none of the uranium would be smuggled to Germany. The route of the secret export of uranium was by rail from the mine to Elisabethville (currently Lubumbashi) to Kolwezi to Lobito port in Angola, and then to the USA by ship. The uranium trade was conducted through secret accounts, and neither the production of the bomb nor the source of the material was known to anyone other than a few top officials.

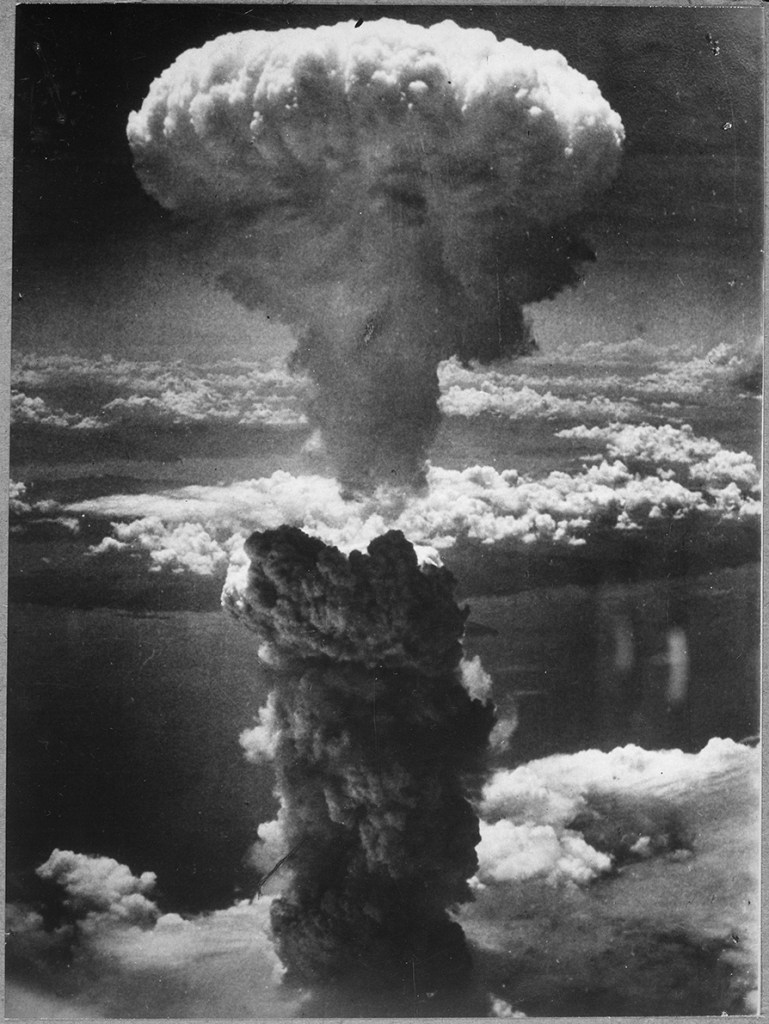

From mid 1944 to early 1945, the victory of Allies was becoming increasingly certain. Although Germany unconditionally surrendered in May 1945, the Manhattan project had continued in full speed because at that time the aim of building atomic bombs had already shifted from surpassing over Nazi Germany to over Communist Soviet Union. The driving force for the Manhattan Project thus became the vision of post-war world domination. On July 16th, the first test of the nuclear weapon was conducted at the Trinity site in New Mexico. The detonation of the plutonium bomb was successful, which reassured the Truman administration that they would not need Stalin’s help to end the war against Japan. This was the best scenario, because if the Soviet Union intervened to defeat Japan, the allies would have to divide the power with the Soviet over Japan. At this point in time, Japan was already seeking a path to end the war and attempting negotiations with the Soviet as an intermediary. But the US allies nevertheless dropped 2 atomic bombs on Japan, one nicknamed Little Boy on Hiroshima on 6th August 1945 and the plutonium bomb Fat Man on Nagasaki on 9th August.

Truman’s speech on August 6th 1945 emphasised Hiroshima city only as an important military base, but didn’t mention that the area was also inhabited fully by civilians. Western media’s repeated use of this selective framing obfuscated the actual destruction and civilian cost in terms of long-lasting effect of the residual radioactivity. Winston Churchill released a statement on the following day on August 7th 1945. The framing and wording meant that it would avoid any mention of the Shinkolobwe mine in Belgian Congo. Instead, The Port Radium Mine in Great Bear Lake in North territory of Canada was deliberately promoted as the only source of uranium used to build those bombs. (The Port Radium was on the indigenous land of Dene people) Churchill stated “The Canadian Government, whose contribution was most valuable, … provided both indispensable raw material for the project as a whole and also necessary facilities for the work on one section of the project”. Congo was never mentioned in any of these speeches.

The atomic bombs killed between 50,000 and 100,000 people instantly. About 210,000 died until December of the same year because of the radioactive exposure. And, it is estimated that, the total A-bomb victims in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were 690,000, of which 10% were people from the Korean peninsula. They had been brought to Japan by the Imperial Japanese Army to work in military factories, or they had lived in Japan in search of work, as life in Korea was no longer livable due to the Japanese colonial rule. In both cases, they were people who should not have been there.

Test On Human Bodies.

In the US today, there are many people who still believe and even prize that the atomic bomb brought an end to fascism and the World War II, but the creation of the bomb was not aiming to bring an “ending” but rather to test its destructive power on the actual human bodies and to research its long lasting effect of radioactivity exposure and finally, as mentioned above, it was to secure the new era of global domination against the Soviet Union. Atomic bombing on the people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki should discussed as part of US’s thousand of nuclear tests. After the defeat of Japan, the US occupation army stationed in Japan censored any criticism of the USA. It also confiscated any photographs of the nuclear disaster documented by Japanese journalists. The US set up the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1946, where the atomic bomb victims were forced to participate in their research without any medical treatment nor shared with the research result. Many corpses were autopsied and preserved in jars with Formaldehyde in the US, until these bodies were returned to Japan in the 1970s. All the research materials were also brought to the US, and the documents were kept secret for 30 years.

Congolese uranium wasn’t only used for the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The US monopoly on Shinkolobwe’s uranium ore and the secrecy culture by the CIA was maintained long after the end of the war. At least, during the first 10 years of the Cold War, Belgian Congo was the main source of uranium for the development of the whole nuclear industry. In this period, several thousands of tons of uranium ore from Shinkolobwe were sold to the US. As a strategy to make sure that none of the Shinkolobwe’s ore fell into the hands of the Soviet Union, the name of Shinkolobwe was erased from any news media reporting about the atomic bomb.

The a-bomb victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki aren’t of course only victims of the US’s nuclear research. For 8 years from 1946, 23 nuclear tests were carried out on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Indigenous people living there were forcibly displaced to another atoll, and then their homes have been forever plundered due to the extreme radioactive contamination. Sixty-four people were also exposed to radiation from the radioactive “death ashes”. In reality, they also became the human material for US’s nuclear research on residual radioactivity.

Above: Archives from Masami Onuka / Courtesy of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, US Army, Nagasaki Museum (the painting by Iri and Toshi Maruki, 母子像 長崎の図 1985

Post-war World Order

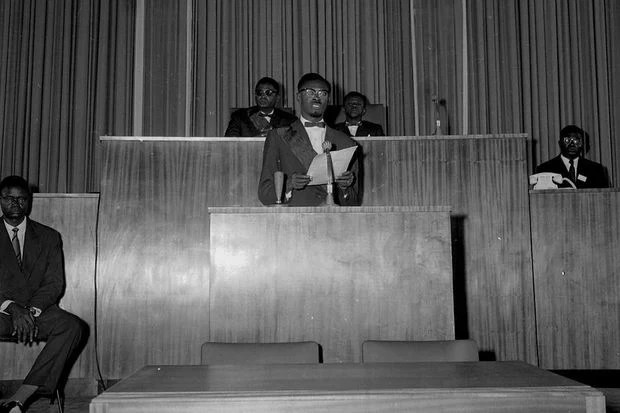

The US control over, and monopoly on, the Shinkolobwe’s uranium ore arguably made it possible for the US to become the most dominant power since 1945. The rapid regrowth of nuclear energy in Europe and Japan is also directly related to this mine. At the end of 1950s, a year before the Congo’s independence, New York businessmen asked Patrice Lumumba, if the Americans could have uranium like they had from Belgians before, and Lumumba answered clearly, “Belgium doesn’t produce uranium… in the future, if the Congo and the United States could make their own agreement, it would be to both our advantage.” This made Belgium furious. Lumumba was elected as the first Prime Minister. Then, just before the independence day, Union Minière sealed off the Shinkolobwe mine with concrete. Lumumba fought for Congolese unity and autonomy, a struggle that needs to be viewed in the context of colonial ties and the mechanisms of exploitation. However, immediately after independence, the Congolese uprising and political upheaval occurred. The Western forces led by Belgium took this chance to secede Katanga from the rest of Congo by using Moïse Thombe. In the midst of the political turmoil induced by the remaining colonial power and intersected with the Cold War, Lumumba was assassinated by the secessionist leaders incl. Belgian officers only 6 months after the independence day. The assassination was plotted and facilitated by the US, Belgium and its allies. Lumumba was killed in so brutal way, which they even dissolved his body in a barrel of acid. Mobutu Sese Seko, who was once an assistant to Lumumba and who led the assassination, took power directly in his second coup in 1965. Despite his loudness about Pan-Africanism, he was in fact a puppet of the West.

(The artist, Roger Peet in ‘Shinkolobwe Between Power and Memory‘ writes about his visit to the site where Lumumba was assacinated: read here. )

Erasure of labourer and ignoring of radioactivity exposure

During the Manhattan project, Congolese miners were forced to work day and night in the open pit at the Shinkolobwe mine. The miners sorted and packed up the uranium ore by hand and sent hundreds of tonnes of them to the USA every month. Suzan William writes in her book that, “according to estimates, they could have been exposed to a year’s worth of radiation in about two weeks… The mine polluted the entire area, affecting the ground and the water supply, and many of the miners’ homes were constructed from radioactive materials.” But none of the effects of radioactivity and their health consequences were archived in Union Minière’s documents. In the 90s, Prof. Donatien Dibwe from Lubumbashi University sought to investigate the working conditions in the Shinkolobwe mine through the archives of Gécamines (successor of UMHK), but he was denied access and told to stop the research (interview conducted by the artist). Gabrielle Hecht, the prominent scholar of nuclear history, mine waste and Anthropocene in Africa, writes in her book ‘Being Nuclear – on the global uranium trade and Africa (2012)’ that, “workers of the Shinkolobwe mine were omitted from the scientific studies on radiation exposure in mining… and the invisibility of their exposure cannot be corrected through archival diligence, because the records – assuming they were even kept – do not appear in the inventory of the Brussels archives.” This book was published more than a decade ago, but according to Dennis Pohl’s article ‘Uranium exposed at Expo 58: the colonial agenda behind the peaceful atom, History and Technology (2021), Union Minière has not yet made its entire archive publicly accessible. The catalogue from 1951-61 is classified as secret until 2050.

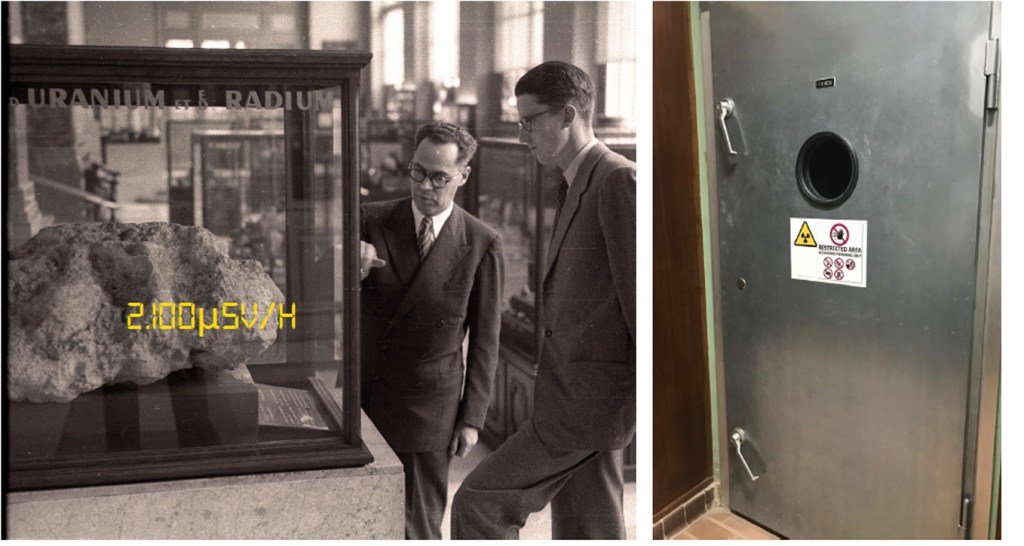

In my conversation with a geologist in Africa Museum Tervuren, Belgium, I learnt that the museum held a collection of 1200 uranium samples. One of the samples is the gigantic uranium block containing uraninite, which was used to be exhibited in the museum. But today no public is allowed to get closer or to even take a single photograph. It is stored in a high secured concrete room. This block itself emits 2100 μSv/h gamma ray of radiation. It means that, if I stand 5mins in front of the stone, I would be exposed to a year’s worth of radiation in 30 mins. But like mentioned above, we can assume the radioactive consequence imposed on the miners, but no official proof can be claimed.

Today, the area around the Shinkolobwe mine is (still) closed to outsiders by the military, state and federal governments. Journalists and scholars are almost never given permission to enter.

(read my monologue of the process of creating radiation images with the uranium samples.)

Contemporary era of the Shinkolobwe mine – From Uranium to Cobalt

The mine shaft in Shinkolobwe was closed down with cement by Union Minière just before the independence of the Congo, but the alleged illegal export of uranium ore dug by artisanal miners would sometimes appear as topics of news. The area is not only rich in uranium, but also in copper and cobalt. As copper and cobalt ores are often mixed with other ore, such as uranium, artisanal diggers in the Shinkolobwe site have been exposed to radioactivity, even though they are not necessarily directly mining uranium ore. Most of these miners, incl. child labourers have no other means to make a living.

In 2014, the deadly collapse of the mine shaft of the Sinkolobwe mine brought world attention to the artisanal mining there. The incident prompted a UN commission to investigate the cause of the accident and radioactive contamination in the area. But the investigation only lasted two weeks and only produced a preliminary list of problems. According to Gabriel Hecht, the UN commission found no large-scale environmental damage and no risk of acute radiation damage, however, UN concluded that the underground miners could have been regularly exposed to significant radioactivity of uranium ore and with radon gas inhalation. This would have resulted in chronic exposure in excess of internationally recognised safe limits for radiation workers. Since then, the Congolese government has shut down the mine and burnt down villages near the Sinkolobwe mine. But it did not stop the artisanal diggers from digging ore in Shinkolobwe. The health damage from radiation has also been confirmed by local researchers. However, it is impossible for them to determine whether chronic health damages are solely due to the radioactivity of uranium, as other ore such as cobalt, is also heavily toxic. Because of the high contamination in their domestic water, birth defect on newborns have been witnessed. However, it is also difficult to attribute such records to a specific mine, because artisanal miners don’t necessarily dig and stay in one mine. (In colonial time, miners were also always mobilised to different mines depend on the company’s need.) Furthermore, such images of birth defects are not publicly available. But we can imagine what could have been going on at Shinkolobwe was also what have been going on nearby mining sites. For example many sickness as well as birth defects have been recognised by doctors in Likasi, about 25 km from Shinkolobwe, and some documents are recorded and made publicly available. (See e.g. documentary from Al Jazeera English about the case at Kolwezi, about 100 km from Shinkolobwe)

For the past 10 years, another industrial mining operation has been rapidly expanding at the of Shinkolobwe. Only 1 km away from the “old” Shinkolobwe mine, 2 of the huge industrial mines have newly opened. This can be seen by satellite maps, by just typing Shinkolobwe mine on Google Map. And, by looking at the timeline of archived satellite maps, we could see the transformation more distinctly, particularly from last year to this year, because one of the mines has become just a double size! In the past 20 years, this area, and the whole of Katanga province, have been occupied by Chinese mining enterprises. To sustain our Global North’s convenient, comfortable and stylish life, Katanga keeps supplying a mass portion of the world’s critical minerals, for every single domestic electronic product like smartphones, computers, products with rechargeable batteries, e-vehicles. But also they are used in the installation of renewable energy for our “green/clean energy”. While the activities all over the world shout to boycott Apple and Tesla, as an Asian I should also bear in mind that, the worst 3 companies that manufacture electronic vehicles, that abuse human rights in their mineral supply chains are; the worst 1. BYD (China), the worst 2. Mitsubishi (Japan) and the worst 3. Hyundai (Korea) in the report of Amnesty International’s on 15 October 2024. In the same month 2024, at the end of the US presidency term, Joe Biden was visiting Angola to rehabilitate and reopen a railway route leading from Katanga’s Copperbelt to the port of Lobito in Angola. This railway used to carry Congolese minerals to export to Belgium during the colonial time and as well as for the Manhattan Project. Katanga is still one of the most important geopolitical sites for the imperial nations’ race for their energy.

Cited References:

Hecht, G. (2012). Being Nuclear: Africans and the Global Uranium Trade, The MIT Press.

Luc Barbé (2012) La Belgique et la bombe: du rêve atomique au rôle secret dans la prolifération nucléaire, Etopia. (In Fr)

Pohl, D (2021) Uranium exposed at Expo 58: the colonial agenda behind the peaceful atom, History and Technology – An International Journal Volume 37, 2021 – Issue 2 https://doi.org/10.1080/07341512.2021.1960074

Williams S, (2016). Spies in the Congo: America’s Atomic Mission in World War II, Public Affairs.

Lewis K. R, (2006 ) A History of Radon 1470 to 1984, https://wpb-radon.com/pdf/History%20of%20Radon.pdf

Relevant literature, Not cited:

Castringius, E (2022). Witnesses to Radioactive Contamination’ from Tracing the Atom,

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003246893-11

Cornum, L (2018). The Irradiated International, Data & Society Research Institute

https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/ii-web.pdf

Hogarth, D. (2014). Robert Rich Sharp (1881–1960), Discoverer of the Shinkolobwe Radium– Uranium Orebodies, Terrae Incognitae, Vol. 46 No. 1, April 2014, 30–41, University of Ottawa,Canada.

Imke C (2021). Sociale Impact can Uraniummijnbouw in Shinkolobwe 1917-1960, BA Thesis, University Ghent (in Dutch)

Peet, R (2023) First They Mined for the Atomic Bomb. Now They’re Mining for E.V.s, The New Republic, August 30, https://newrepublic.com/article/174374/first-mined-atomic-bomb-nowtheyre-mining-evs.

Takahashi H, (2012)Classified Hiroshima and Nagasaki: U.S. Nuclear Test and Civil Defence Programme (Hūinsareta Hiroshima. Nagasaki, Beikakuzikken to Minkanboueikeikaku), Gaihūsha (in JP)